“1 Maintenance Coordinator Can Handle 2k Doors” [BARF SOUND]

Breaking the 1 Coordinator, 200-Door Ceiling Without Burning Out

🎧 Listen to the Audio Version

Last week, I was conducting a focus group with four of my favorite people in property management, including Jen Ruelens. She runs a ~600-door property management company, and she was walking me through the trials and tribulations of building her maintenance department.

At one point, after listening to everything she already had in place, I said something she found outright repulsive.:

“I think one person could responsibly run 2,000 doors.”

She made a gesture like she was about to throw up on herself. Classic PMJen physical comedy. But the reaction wasn’t a joke.

She’s heard too many big claims before. Too many people who had never walked her buildings, never sat in owner conversations, never carried the weight of maintenance decisions, telling her what should be possible.

And now AI is here- and the world (beyond vendors) is telling this is a real promise- which somehow makes the skepticism worse, not better. Because if the work underneath doesn’t change, neither do the limits: burnout, capacity ceilings, and the quiet acceptance that growth always comes with pain.

But here’s the part that gets missed-

The idea that one person could responsibly own outcomes at that scale didn’t come from a pitch deck. It didn’t start with AI. And it wasn’t imagined by someone who hadn’t experienced the problem (like me).

It came from a guy who built a 600 door property management company from scratch in 4 years. It came from a guy who maintained tens of thousands of doors for Fannie and Freddie’s REO portfolio post Great Recession.

The claim came from David Normand. And the legitimacy of his claim doesn’t come from his past successes. It comes from where he failed.

Curious how Vendoroo actually works? Here’s my best attempt at making it simple.

The 80 To 600 Door Scale & “Fail”

David didn’t arrive at his conclusions through theory or frameworks. He earned them by building.

Over roughly four years in New England, he grew a property management operation from about 80 doors to more than 600. The operation scaled quickly, but it did not scale blindly. David stayed deeply involved in maintenance decisions, and owners trusted that involvement. His judgment was the actual product.

For a long time, that was enough.

As the portfolio approached 500 doors, the strain did not show up as missed tickets or unavailable vendors. It surfaced in quieter places, in the moments that never make it into SOPs.

Around the 500–600 door mark, the failures weren’t visible in the system. They showed up in moments like this:

- An owner had just spent over $12,000 on a roof after a compliance issue. The next maintenance request was technically routine, under NTE, and eligible for immediate dispatch.

- The system said “send it.” David knew the owner needed restraint, context, and a conversation before another dollar went out the door.

- Once that decision had to pass through layers of people, the nuance thinned. The ticket was closed.. The process was followed. The trust wasn’t.

From the outside, the operation still looked like a success. Six hundred doors. Strong processes. A capable team.

But David did not measure success by volume or ticket throughput. He measured it by whether judgment still showed up when it mattered most.

He could have lowered the bar. Tightened rules. Accepted that this was simply the cost of scale.

He didn’t.

What he had built was good enough to scale, and precise enough to reveal exactly where and why it stopped working for him.

And that’s why his system is so useful to understand.

The FedEx Method: How Judgment Was Turned Into Process

What David built next wasn’t accidental, and it wasn’t naïve. It was a serious attempt to make a judgment scale.

He called it the FedEx Method.

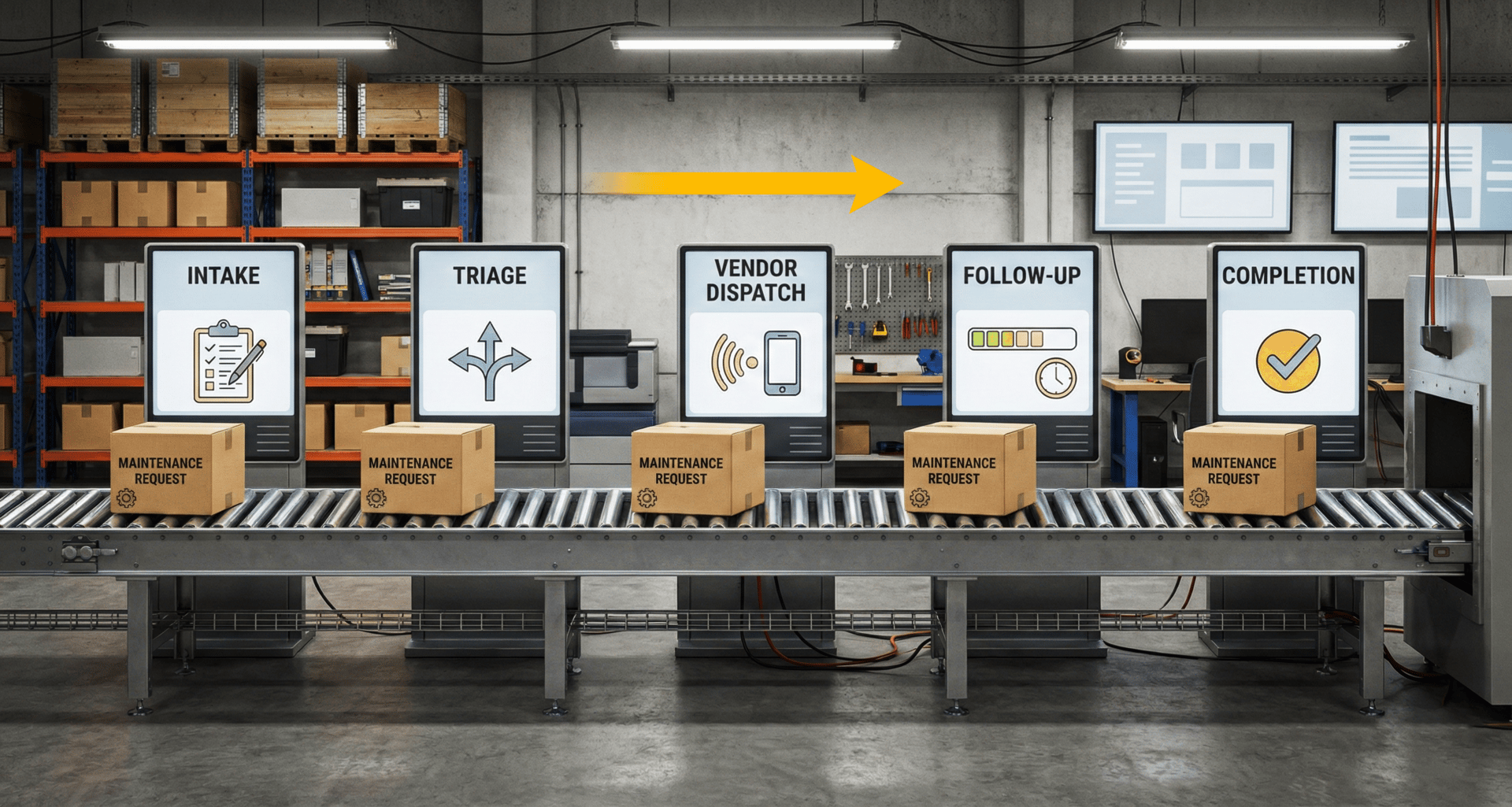

David used to sketch it on a legal pad: a conveyor belt moving from left to right. Every maintenance request entered the belt as a box. Along the way, the box passed through a series of stations—intake, triage, vendor coordination, follow-up, completion. At each station, something specific had to happen before the box could move forward.

The insight wasn’t the belt itself. It was the realization that the work moving across it wasn’t uniform.

Some of the belts were defined work. Logging requests, sending updates, following up with vendors, closing documentation. The kind of work that needs to be done the same way every time so nothing breaks.

Other moments were undefined work.. Knowing when to call an owner even if the system didn’t require it. Sensing when a vendor quote felt off. Stepping in early to prevent a relationship from quietly eroding.

Those moments couldn’t be scheduled or scripted. They lived in context./

Watch Tony Cline and Darus Trutna discuss the nuances of defined vs undefined work (36:20) on the Property Management Success Podcast.

The brilliance of the FedEx Method was that it separated these two types of work, helping maintenance coordinators crank through the defined work, while bringing David in to intervene during the undefined moments.

Since roughly 80-85% of property management tasks fall into the “defined work” bucket, you could say David achieved 80-85% levels of automation.

We just don’t think of leverage through human labor as automation, but it’s essentially the same result as an operator. And for a long time, the FedEx conveyor belt moved cleanly.

So what went wrong? Human labor physics.

When Defined Work Eclipses Judgment

The problem wasn’t the belt. It was what the belt produced.

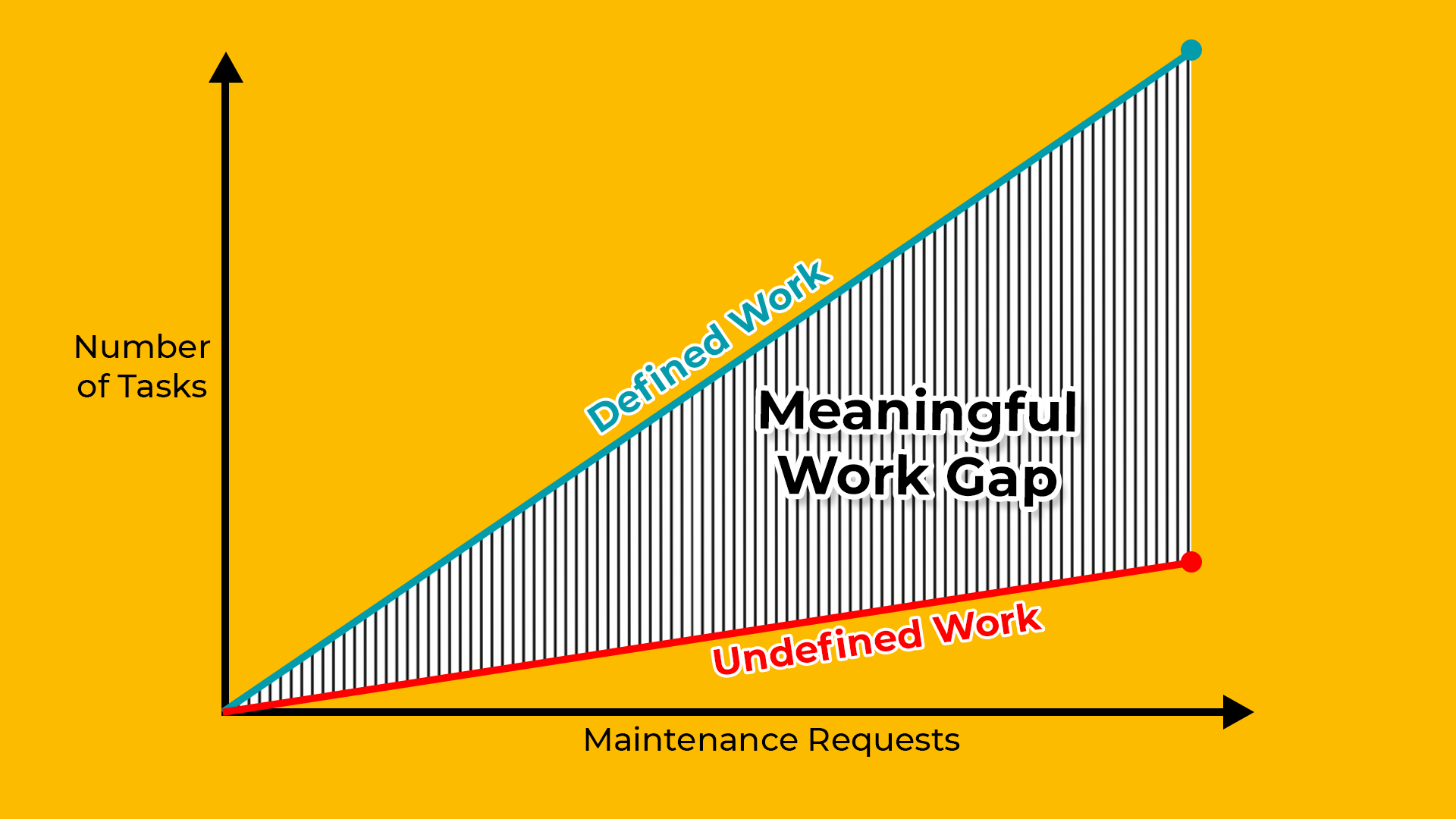

As David’s operation grew, the balance of work shifted. Every additional door added a small amount of judgment, but it added a much larger amount of defined work.

More tickets led to more updates, more follow-ups, more documentation, and more coordination just to keep things from stalling.

To keep the system running, David did what any rational operator would do. He hired for the work that was exploding. Detail-oriented people who could track dozens of moving pieces, keep a high standard, and own outcomes..

It worked. And then it didn’t.

The same people capable of sustaining that level of performance are the type of people that look for meaning in their work. But over time, their days filled with follow-ups, status changes, and confirmations. Judgment became rare. Endurance became the job.

The pattern was predictable. Boredom set in. Burnout followed. Turnover came next.

As Darus Trutna put it in his conversation with Tony Cline:

“We all have a desire to be of value, and when we don’t do that, we have depressive cycles.”

This wasn’t a hiring failure. David was putting the right people in the right seats. It wasn’t a management failure either. The system was simply asking humans to carry a volume of defined work that expanded faster than human capacity ever could.

That was the real ceiling.

Every departure carried a hidden cost. Trained talent walked out the door. Earned judgement disappeared. The belt kept moving, but it grew heavier each time.

David would later manage maintenance at a massive institutional scale, with the ability to add hundreds of people if needed. The ceiling still didn’t move beyond roughly 200 doors per maintenance coordinator.

It wasn’t process. It wasn’t effort.

It was human physics.

Letting the Belt Run With A Different Motor: Agentic AI

For David, the breakthrough was not speed. It was structured.

The problem he kept running into was framed as a people problem or a process problem when it was really a physics problem. Judgment and coordination- undefined and defined work- were bound together, and every attempt to preserve one quietly consumed the other.

The insight that changed everything was simple but radical:

Agentic AI gives us the ability to spare humans from the avalanche of defined work.

For the first time, there was a way to let the conveyor belt keep moving without exhausting the people standing next to it. By teaching AI agents the logic of the belt- intake, routing, follow-ups, updates, closure- the work that had once demanded constant human attention could finally run without fatigue, boredom, or loss of meaning.

“The breakthrough isn’t replacing good people or systems that already work,” David said. “It’s removing the parts of the job that were pushing good people out.”

That shift changed the shape of the operation.

As the Chief Property Manager at Vendoroo, David has spent the last 2 years pouring through hundreds of thousands of work order tickets, and training the ROO AI how to make decisions the way he trained his maintenance staff throughout his career.

What he has seen is even more meaningful than a 10x capacity:

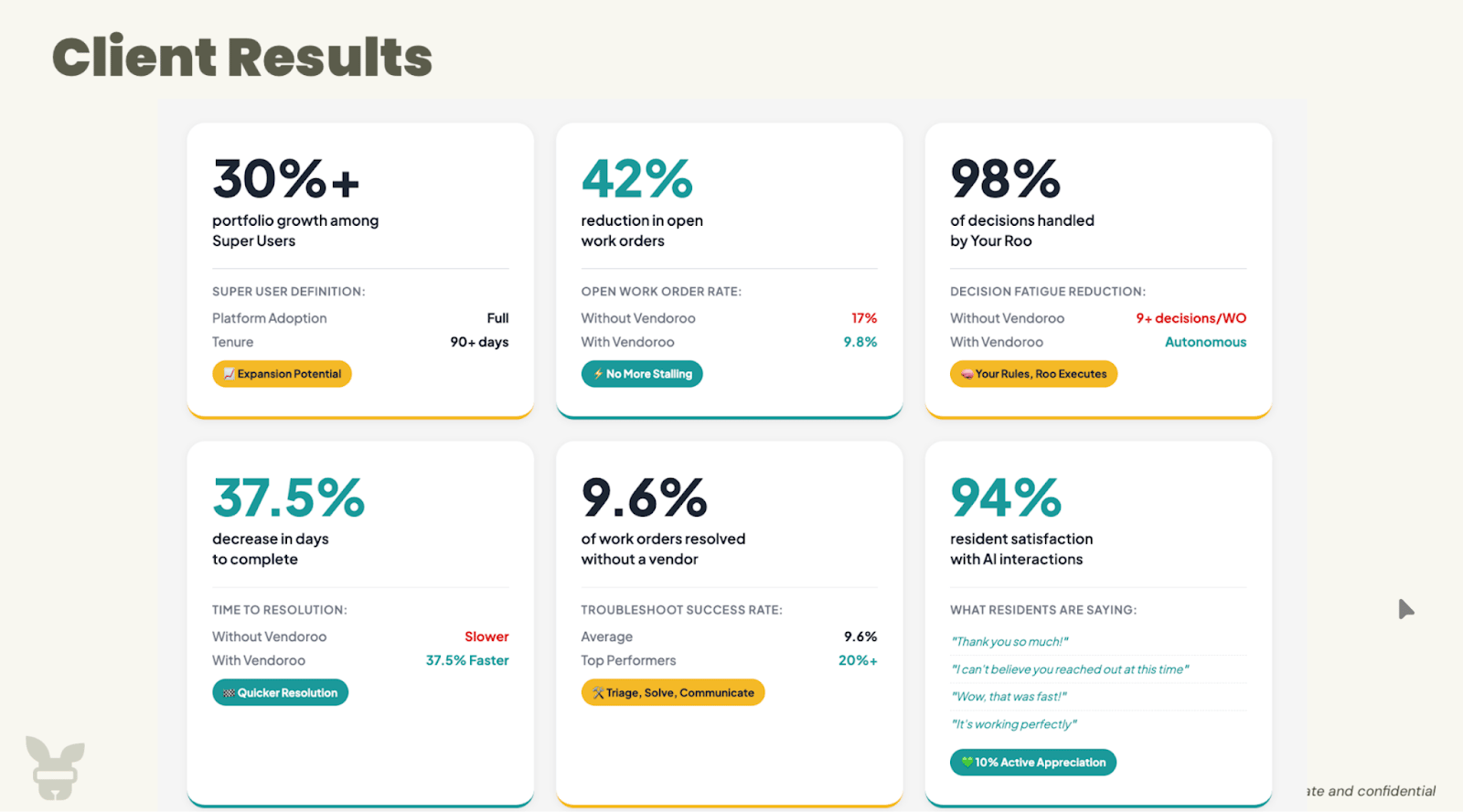

- ROO’s ability to handle multiple defined actions at once has led to a 40% reduction in open work orders

- ROO’s 24/7 availability has led to a 37.5% decrease in days to complete maintenance issues

- ROO’s ability to learn, implement, and never forget has led to its ability to handle 98% of the touchpoints on the conveyor belt

And when the defined work disappeared from human plates, something changed for the teams using Vendoroo.

Judgment has resurfaced.

People have space to:

- Verify pricing before discussing an expensive item with an owner

- Check in on vendors that are falling behind and find alternatives

- Focus on growth levers instead of maintenance belts

Dave now sits front row, watching his previous ceiling of 200 doors being shattered by his clients. He sees a new standard of capacity: 2,000 doors per maintenance coordinator.

The belt did not disappear. It simply stopped requiring people to push it.

And for the first time, judgment could scale without breaking the person holding it.

Why This Time Is Different

When I told Jen that one person could responsibly own outcomes across 2,000 doors, her reaction wasn’t disbelief. It was self-protection.

She’s been promised leverage before. Faster software. Smarter dashboards. Better coordination layered on top of the same work. Each time, the story ended the same way: more speed, more noise, the same ceilings, and the same human cost.

This feels different not because the claim is bigger, but because the reasoning underneath it finally matches reality.

No one here is pretending maintenance got easier. No one is claiming judgment can be automated away. And no one is suggesting that great operators were doing it wrong all along.

The opposite is true.

The 2,000-door standard comes from taking the best operators seriously. From accepting that great systems and great people really do work, right up to the point where human physics takes over.

From acknowledging that burnout, churn, and capacity ceilings were never moral failures or management gaps. They were structural limits.

Agentic AI does not replace that wisdom. It absorbs the work that was never worthy of it.

When defined work is carried by systems instead of people, judgment stops being crowded out. When judgment has room to operate, ownership can scale without heroics. And when ownership can scale without pain, capacity finally moves.

That’s why this isn’t a promise.

It’s a diagnostic.

If one person cannot responsibly own outcomes at scale without burning out, the system has not changed yet. The belt is still being pushed.

For the first time, it doesn’t have to be.

Pablo Gonzalez

Chief Evangelist at Vendoroo

P.S. Would love to show you how Vendoroo can help your team break through the physics of human effort for you. Book a demo.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)